I had the pleasure of attending Richard Dawkins’ Oxford lecture on his Genetic Book of the Dead tour on 21 October 2024. Dawkins describes this as his final tour—although, fortunately, unlike the tour, this book won’t be his last. The talk featured Alex O’Connor, a rising philosopher whose YouTube presence has attracted a following and given him access to several high-profile guests.

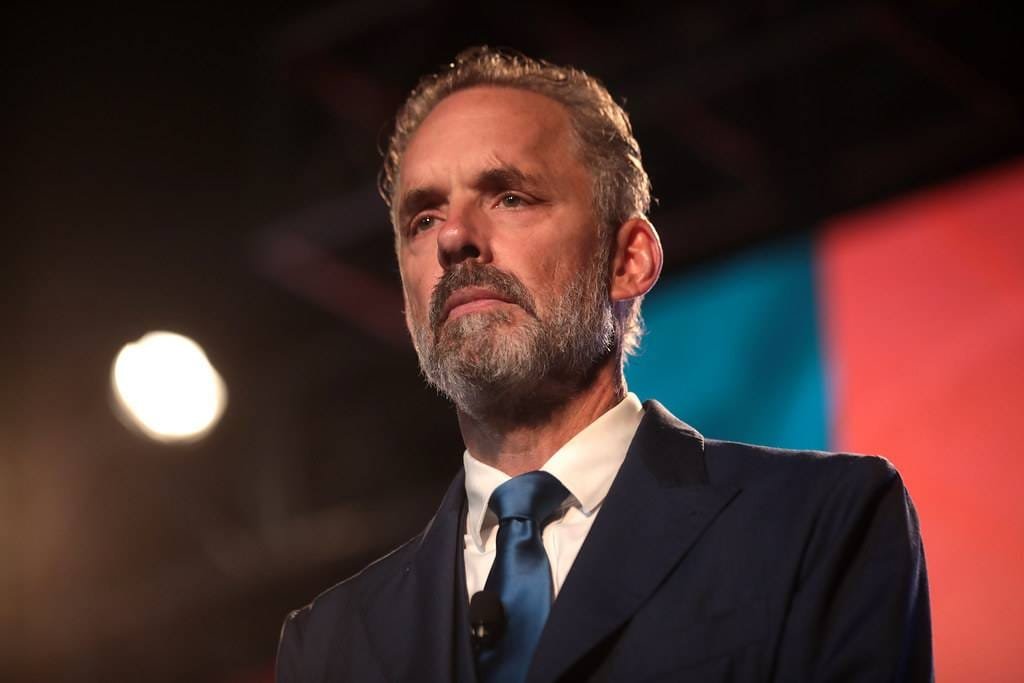

Initially, the discussion focused on Dawkins’ newest book, but—as is often the case with Dawkins—it quickly veered into the provocative territory where societal norms and dogmas come under fire. Questions delved into his New Atheism and broader secular ideas, eventually leading to the controversial figure, Jordan Peterson. I had long been a follower of Dawkins’ work before Peterson entered the public sphere, and I continue to admire Dawkins’ relentless pursuit of truth. Peterson, on the other hand, first came to my attention around 2016. I recall seeing a video thumbnail of him at a protest related to Bill C-16, where he was addressing the fraught issue of compelled speech versus free speech—a stance that resonated with me and, in fact, with many other advocates of free expression, including Dawkins himself. I found Peterson’s perspective compelling and watched his content avidly for the next few years.

Yet over time, I grew disillusioned with Peterson’s consistent defence of religion and what could only be described as a kind of mythical thinking. Rather than addressing questions of truth or fact directly, he would evade them, plunging into philosophical tangents that seemed designed to justify belief for its own sake. At a certain point, I stopped following his work—and indeed withdrew from much intellectual engagement altogether—as personal matters came to the forefront. In hindsight, this period allowed me to reassess my own positions, though I have always been inclined towards a more centrist and nuanced political outlook. Eventually, I came to see Peterson as overly beholden to traditionalism, often associating with rigid right-wing conservatives. For someone like myself who despises partisan traps, this was enough to make me reconsider my admiration.

Sam Harris, another figure in these intellectual circles, has notably criticised such partisanship, eventually distancing himself from the so-called Intellectual Dark Web (IDW) due to its pseudo-intellectualism and partisan undercurrents. I still recall Harris’ and Peterson’s first podcast discussion on truth, where Peterson’s performance was particularly cringeworthy; it exposed a troubling lack of empiricism and a surprising indifference to how we should best measure truth. For all of Peterson’s rhetorical tangents and verbose monologues, his justification of religiosity and myth never convinced me, and his rigid traditionalist stance only deepened my disinterest.

Peterson’s primary defect on this topic is, as I see it, is his fixation on metaphors, symbols, and stories—and the cultural values he perceives in them—rather than examining whether these tales hold any empirical truth. He seems intent on keeping these narratives alive for their supposed “meaning,” as if society’s well-being depends on perpetuating these comfortable illusions yet human history has clearly shown that the more we move away from these mythical delusions, the better we progress. I cannot escape the impression that he is pandering to people’s gullibility, indulging their desire for comforting myths over hard truths. And yes, people are indeed gullible and fickle (a sentiment Peterson might resist, as with most people, though I would not). But if we are to progress, to evolve as a society, then clinging to myth and superstition is anathema to progress and improvement.

Peterson’s intellectual conflict between fact and fiction is evident in his tendency to conflate the two, all while fixating obsessively on stories as a vehicle for truth. He routinely places Christianity at the centre of his cultural metaphors, as though this particular faith tradition alone is the blueprint for societal values.

Observing the online comments from his followers, I frequently come across individuals who claim to have once been atheists and drawn to figures like Dawkins, only to have returned to religion, or at least grown more sympathetic to it, through Peterson’s abstract reasoning. I believe that many of these people are captivated by his guru-like ramblings, grasping at his abstractions as a response to their frustrations with sociocultural issues, including “wokery.” If anything, these followers reveal themselves to be weak-minded, retreating into the comfort of faith to escape the uncomfortable truth of human insignificance. And yes, I’d imagine such a statement would set their egos alight.

As for myself, I’m concerned with facts, not fictions. Fictions are to be enjoyed as art, not regarded as truth. They might reflect aspects of reality, as in Star Wars, where the Galactic Empire symbolises oppressive power and Anakin’s fall exemplifies emotional weakness. Yet these are ultimately fictions, expanded and exaggerated from the real world, rife with supernatural elements and impossibilities. Stories, of course, can offer values and insights, but these stem from imagination rooted in experience. Why, then, must we—as Peterson does—fixate on Christianity alone? The same moral archetypes are present in countless other mythologies, each equally imaginative and equally fictional. Once again, they remain just that: stories, which we should acknowledge as such. A moral lesson derived from a story does not, in itself, grant that story any empirical truth.

*This is an essay that will likely be featured in an upcoming book.

[{"id":1589,"link":"https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/anxiety-austerity-and-a-punishing-society\/","name":"anxiety-austerity-and-a-punishing-society","thumbnail":{"url":"https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/wp-content\/uploads\/2025\/12\/jknkjnk.jpg","alt":""},"title":"Anxiety, Austerity and a Punishing Society","postMeta":[],"author":{"name":"Daniel Brynmor","link":"https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/author\/braiddunig\/"},"date":"Dec 19, 2025","dateGMT":"2025-12-19 11:41:51","modifiedDate":"2025-12-19 11:41:53","modifiedDateGMT":"2025-12-19 11:41:53","commentCount":"0","commentStatus":"open","categories":{"coma":"<a href=\"https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/category\/essays\/\" rel=\"category tag\">Essays<\/a>","space":"<a href=\"https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/category\/essays\/\" rel=\"category tag\">Essays<\/a>"},"taxonomies":{"post_tag":"<a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/antitheism\/' rel='post_tag'>Antitheism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/articles\/' rel='post_tag'>Articles<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/atheism\/' rel='post_tag'>Atheism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/being\/' rel='post_tag'>being<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/contemporary-philosophy\/' rel='post_tag'>contemporary philosophy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/critique\/' rel='post_tag'>critique<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/crowd-psychology\/' rel='post_tag'>Crowd Psychology<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/culture\/' rel='post_tag'>culture<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/cynicism\/' rel='post_tag'>Cynicism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/epistemology\/' rel='post_tag'>Epistemology<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/essays\/' rel='post_tag'>Essays<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/ethics\/' rel='post_tag'>Ethics<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/existentialism\/' rel='post_tag'>Existentialism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/herd-mentality\/' rel='post_tag'>Herd Mentality<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/human-condition\/' rel='post_tag'>Human Condition<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/human-nature\/' rel='post_tag'>Human Nature<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/maxims\/' rel='post_tag'>Maxims<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/mental-health\/' rel='post_tag'>Mental Health<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/metaphysics\/' rel='post_tag'>Metaphysics<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/misanthropy\/' rel='post_tag'>Misanthropy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/moral-philosophy\/' rel='post_tag'>Moral Philosophy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/morality\/' rel='post_tag'>Morality<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/musings\/' rel='post_tag'>Musings<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/nihilism\/' rel='post_tag'>Nihilism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/philosophical-pessimism\/' rel='post_tag'>philosophical pessimism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/philosophy\/' rel='post_tag'>Philosophy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/philosophy-of-mind\/' rel='post_tag'>Philosophy of Mind<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/polemics\/' rel='post_tag'>polemics<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/political-philosophy\/' rel='post_tag'>Political Philosophy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/politics\/' rel='post_tag'>politics<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/reflections\/' rel='post_tag'>Reflections<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/science\/' rel='post_tag'>science<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/secularism\/' rel='post_tag'>secularism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/social-philosophy\/' rel='post_tag'>Social Philosophy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/social-psychology\/' rel='post_tag'>Social Psychology<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/society\/' rel='post_tag'>society<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/stoicism\/' rel='post_tag'>Stoicism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/the-self\/' rel='post_tag'>the self<\/a>"},"readTime":{"min":4,"sec":9},"status":"publish","excerpt":""},{"id":1577,"link":"https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/how-society-punishes-eccentricity\/","name":"how-society-punishes-eccentricity","thumbnail":{"url":"https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/wp-content\/uploads\/2025\/02\/Brynmor-in-the-library.jpg","alt":""},"title":"How Society Punishes Eccentricity","postMeta":[],"author":{"name":"Daniel Brynmor","link":"https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/author\/braiddunig\/"},"date":"Feb 10, 2025","dateGMT":"2025-02-10 11:42:04","modifiedDate":"2025-02-10 11:42:13","modifiedDateGMT":"2025-02-10 11:42:13","commentCount":"0","commentStatus":"open","categories":{"coma":"<a href=\"https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/category\/essays\/\" rel=\"category tag\">Essays<\/a>","space":"<a href=\"https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/category\/essays\/\" rel=\"category tag\">Essays<\/a>"},"taxonomies":{"post_tag":"<a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/antitheism\/' rel='post_tag'>Antitheism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/articles\/' rel='post_tag'>Articles<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/atheism\/' rel='post_tag'>Atheism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/being\/' rel='post_tag'>being<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/contemporary-philosophy\/' rel='post_tag'>contemporary philosophy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/critique\/' rel='post_tag'>critique<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/crowd-psychology\/' rel='post_tag'>Crowd Psychology<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/culture\/' rel='post_tag'>culture<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/cynicism\/' rel='post_tag'>Cynicism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/epistemology\/' rel='post_tag'>Epistemology<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/essays\/' rel='post_tag'>Essays<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/ethics\/' rel='post_tag'>Ethics<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/existentialism\/' rel='post_tag'>Existentialism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/herd-mentality\/' rel='post_tag'>Herd Mentality<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/human-condition\/' rel='post_tag'>Human Condition<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/human-nature\/' rel='post_tag'>Human Nature<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/maxims\/' rel='post_tag'>Maxims<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/mental-health\/' rel='post_tag'>Mental Health<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/metaphysics\/' rel='post_tag'>Metaphysics<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/misanthropy\/' rel='post_tag'>Misanthropy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/moral-philosophy\/' rel='post_tag'>Moral Philosophy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/morality\/' rel='post_tag'>Morality<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/musings\/' rel='post_tag'>Musings<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/nihilism\/' rel='post_tag'>Nihilism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/philosophical-pessimism\/' rel='post_tag'>philosophical pessimism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/philosophy\/' rel='post_tag'>Philosophy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/philosophy-of-mind\/' rel='post_tag'>Philosophy of Mind<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/polemics\/' rel='post_tag'>polemics<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/political-philosophy\/' rel='post_tag'>Political Philosophy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/politics\/' rel='post_tag'>politics<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/reflections\/' rel='post_tag'>Reflections<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/science\/' rel='post_tag'>science<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/secularism\/' rel='post_tag'>secularism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/social-philosophy\/' rel='post_tag'>Social Philosophy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/social-psychology\/' rel='post_tag'>Social Psychology<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/society\/' rel='post_tag'>society<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/stoicism\/' rel='post_tag'>Stoicism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/the-self\/' rel='post_tag'>the self<\/a>"},"readTime":{"min":0,"sec":55},"status":"publish","excerpt":""},{"id":1574,"link":"https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/the-superficiality-of-the-social-hierarchy\/","name":"the-superficiality-of-the-social-hierarchy","thumbnail":{"url":"https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/wp-content\/uploads\/2025\/02\/minimalist-art-depicting-someone-tripping-people-up-to-get-ahead.jpg","alt":""},"title":"The Superficiality of the Social Hierarchy","postMeta":[],"author":{"name":"Daniel Brynmor","link":"https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/author\/braiddunig\/"},"date":"Feb 10, 2025","dateGMT":"2025-02-10 11:37:32","modifiedDate":"2025-02-10 11:37:41","modifiedDateGMT":"2025-02-10 11:37:41","commentCount":"0","commentStatus":"open","categories":{"coma":"<a href=\"https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/category\/essays\/\" rel=\"category tag\">Essays<\/a>","space":"<a href=\"https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/category\/essays\/\" rel=\"category tag\">Essays<\/a>"},"taxonomies":{"post_tag":"<a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/antitheism\/' rel='post_tag'>Antitheism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/articles\/' rel='post_tag'>Articles<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/atheism\/' rel='post_tag'>Atheism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/being\/' rel='post_tag'>being<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/contemporary-philosophy\/' rel='post_tag'>contemporary philosophy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/critique\/' rel='post_tag'>critique<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/crowd-psychology\/' rel='post_tag'>Crowd Psychology<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/culture\/' rel='post_tag'>culture<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/cynicism\/' rel='post_tag'>Cynicism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/epistemology\/' rel='post_tag'>Epistemology<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/essays\/' rel='post_tag'>Essays<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/ethics\/' rel='post_tag'>Ethics<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/existentialism\/' rel='post_tag'>Existentialism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/herd-mentality\/' rel='post_tag'>Herd Mentality<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/human-condition\/' rel='post_tag'>Human Condition<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/human-nature\/' rel='post_tag'>Human Nature<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/maxims\/' rel='post_tag'>Maxims<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/mental-health\/' rel='post_tag'>Mental Health<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/metaphysics\/' rel='post_tag'>Metaphysics<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/misanthropy\/' rel='post_tag'>Misanthropy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/moral-philosophy\/' rel='post_tag'>Moral Philosophy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/morality\/' rel='post_tag'>Morality<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/musings\/' rel='post_tag'>Musings<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/nihilism\/' rel='post_tag'>Nihilism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/philosophical-pessimism\/' rel='post_tag'>philosophical pessimism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/philosophy\/' rel='post_tag'>Philosophy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/philosophy-of-mind\/' rel='post_tag'>Philosophy of Mind<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/polemics\/' rel='post_tag'>polemics<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/political-philosophy\/' rel='post_tag'>Political Philosophy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/politics\/' rel='post_tag'>politics<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/reflections\/' rel='post_tag'>Reflections<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/science\/' rel='post_tag'>science<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/secularism\/' rel='post_tag'>secularism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/social-philosophy\/' rel='post_tag'>Social Philosophy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/social-psychology\/' rel='post_tag'>Social Psychology<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/society\/' rel='post_tag'>society<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/stoicism\/' rel='post_tag'>Stoicism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/the-self\/' rel='post_tag'>the self<\/a>"},"readTime":{"min":1,"sec":14},"status":"publish","excerpt":""},{"id":1532,"link":"https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/jumping-on-the-bandwagon\/","name":"jumping-on-the-bandwagon","thumbnail":{"url":"https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/wp-content\/uploads\/2025\/02\/b.png","alt":""},"title":"Jumping on the Bandwagon","postMeta":[],"author":{"name":"Daniel Brynmor","link":"https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/author\/braiddunig\/"},"date":"Feb 5, 2025","dateGMT":"2025-02-05 20:41:24","modifiedDate":"2025-02-05 20:41:31","modifiedDateGMT":"2025-02-05 20:41:31","commentCount":"0","commentStatus":"open","categories":{"coma":"<a href=\"https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/category\/essays\/\" rel=\"category tag\">Essays<\/a>","space":"<a href=\"https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/category\/essays\/\" rel=\"category tag\">Essays<\/a>"},"taxonomies":{"post_tag":"<a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/antitheism\/' rel='post_tag'>Antitheism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/articles\/' rel='post_tag'>Articles<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/atheism\/' rel='post_tag'>Atheism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/being\/' rel='post_tag'>being<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/contemporary-philosophy\/' rel='post_tag'>contemporary philosophy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/critique\/' rel='post_tag'>critique<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/crowd-psychology\/' rel='post_tag'>Crowd Psychology<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/culture\/' rel='post_tag'>culture<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/cynicism\/' rel='post_tag'>Cynicism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/epistemology\/' rel='post_tag'>Epistemology<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/essays\/' rel='post_tag'>Essays<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/ethics\/' rel='post_tag'>Ethics<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/existentialism\/' rel='post_tag'>Existentialism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/herd-mentality\/' rel='post_tag'>Herd Mentality<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/human-condition\/' rel='post_tag'>Human Condition<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/human-nature\/' rel='post_tag'>Human Nature<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/maxims\/' rel='post_tag'>Maxims<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/mental-health\/' rel='post_tag'>Mental Health<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/metaphysics\/' rel='post_tag'>Metaphysics<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/misanthropy\/' rel='post_tag'>Misanthropy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/moral-philosophy\/' rel='post_tag'>Moral Philosophy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/morality\/' rel='post_tag'>Morality<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/musings\/' rel='post_tag'>Musings<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/nihilism\/' rel='post_tag'>Nihilism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/philosophical-pessimism\/' rel='post_tag'>philosophical pessimism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/philosophy\/' rel='post_tag'>Philosophy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/philosophy-of-mind\/' rel='post_tag'>Philosophy of Mind<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/polemics\/' rel='post_tag'>polemics<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/political-philosophy\/' rel='post_tag'>Political Philosophy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/politics\/' rel='post_tag'>politics<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/reflections\/' rel='post_tag'>Reflections<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/science\/' rel='post_tag'>science<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/secularism\/' rel='post_tag'>secularism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/social-philosophy\/' rel='post_tag'>Social Philosophy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/social-psychology\/' rel='post_tag'>Social Psychology<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/society\/' rel='post_tag'>society<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/stoicism\/' rel='post_tag'>Stoicism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/the-self\/' rel='post_tag'>the self<\/a>"},"readTime":{"min":1,"sec":52},"status":"publish","excerpt":""},{"id":1521,"link":"https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/you-are-shaped-by-external-influence\/","name":"you-are-shaped-by-external-influence","thumbnail":{"url":"https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/wp-content\/uploads\/2025\/02\/njn.jpeg","alt":""},"title":"You Are Shaped by External Influence","postMeta":[],"author":{"name":"Daniel Brynmor","link":"https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/author\/braiddunig\/"},"date":"Feb 5, 2025","dateGMT":"2025-02-05 20:33:52","modifiedDate":"2025-02-05 20:33:58","modifiedDateGMT":"2025-02-05 20:33:58","commentCount":"0","commentStatus":"open","categories":{"coma":"<a href=\"https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/category\/essays\/\" rel=\"category tag\">Essays<\/a>","space":"<a href=\"https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/category\/essays\/\" rel=\"category tag\">Essays<\/a>"},"taxonomies":{"post_tag":"<a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/antitheism\/' rel='post_tag'>Antitheism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/articles\/' rel='post_tag'>Articles<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/atheism\/' rel='post_tag'>Atheism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/being\/' rel='post_tag'>being<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/contemporary-philosophy\/' rel='post_tag'>contemporary philosophy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/critique\/' rel='post_tag'>critique<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/crowd-psychology\/' rel='post_tag'>Crowd Psychology<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/culture\/' rel='post_tag'>culture<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/cynicism\/' rel='post_tag'>Cynicism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/epistemology\/' rel='post_tag'>Epistemology<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/essays\/' rel='post_tag'>Essays<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/ethics\/' rel='post_tag'>Ethics<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/existentialism\/' rel='post_tag'>Existentialism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/herd-mentality\/' rel='post_tag'>Herd Mentality<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/human-condition\/' rel='post_tag'>Human Condition<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/human-nature\/' rel='post_tag'>Human Nature<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/maxims\/' rel='post_tag'>Maxims<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/mental-health\/' rel='post_tag'>Mental Health<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/metaphysics\/' rel='post_tag'>Metaphysics<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/misanthropy\/' rel='post_tag'>Misanthropy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/moral-philosophy\/' rel='post_tag'>Moral Philosophy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/morality\/' rel='post_tag'>Morality<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/musings\/' rel='post_tag'>Musings<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/nihilism\/' rel='post_tag'>Nihilism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/philosophical-pessimism\/' rel='post_tag'>philosophical pessimism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/philosophy\/' rel='post_tag'>Philosophy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/philosophy-of-mind\/' rel='post_tag'>Philosophy of Mind<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/polemics\/' rel='post_tag'>polemics<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/political-philosophy\/' rel='post_tag'>Political Philosophy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/politics\/' rel='post_tag'>politics<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/reflections\/' rel='post_tag'>Reflections<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/science\/' rel='post_tag'>science<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/secularism\/' rel='post_tag'>secularism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/social-philosophy\/' rel='post_tag'>Social Philosophy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/social-psychology\/' rel='post_tag'>Social Psychology<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/society\/' rel='post_tag'>society<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/stoicism\/' rel='post_tag'>Stoicism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/the-self\/' rel='post_tag'>the self<\/a>"},"readTime":{"min":2,"sec":33},"status":"publish","excerpt":""},{"id":1515,"link":"https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/slaves-to-cultic-behaviour\/","name":"slaves-to-cultic-behaviour","thumbnail":{"url":"https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/wp-content\/uploads\/2025\/01\/afasfasf.png","alt":""},"title":"Slaves to Cultic Behaviour","postMeta":[],"author":{"name":"Daniel Brynmor","link":"https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/author\/braiddunig\/"},"date":"Jan 30, 2025","dateGMT":"2025-01-30 20:55:47","modifiedDate":"2025-01-30 20:55:55","modifiedDateGMT":"2025-01-30 20:55:55","commentCount":"0","commentStatus":"open","categories":{"coma":"<a href=\"https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/category\/essays\/\" rel=\"category tag\">Essays<\/a>","space":"<a href=\"https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/category\/essays\/\" rel=\"category tag\">Essays<\/a>"},"taxonomies":{"post_tag":"<a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/antitheism\/' rel='post_tag'>Antitheism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/articles\/' rel='post_tag'>Articles<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/atheism\/' rel='post_tag'>Atheism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/being\/' rel='post_tag'>being<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/contemporary-philosophy\/' rel='post_tag'>contemporary philosophy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/critique\/' rel='post_tag'>critique<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/crowd-psychology\/' rel='post_tag'>Crowd Psychology<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/culture\/' rel='post_tag'>culture<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/cynicism\/' rel='post_tag'>Cynicism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/epistemology\/' rel='post_tag'>Epistemology<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/essays\/' rel='post_tag'>Essays<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/ethics\/' rel='post_tag'>Ethics<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/existentialism\/' rel='post_tag'>Existentialism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/herd-mentality\/' rel='post_tag'>Herd Mentality<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/human-condition\/' rel='post_tag'>Human Condition<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/human-nature\/' rel='post_tag'>Human Nature<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/maxims\/' rel='post_tag'>Maxims<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/mental-health\/' rel='post_tag'>Mental Health<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/metaphysics\/' rel='post_tag'>Metaphysics<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/misanthropy\/' rel='post_tag'>Misanthropy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/moral-philosophy\/' rel='post_tag'>Moral Philosophy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/morality\/' rel='post_tag'>Morality<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/musings\/' rel='post_tag'>Musings<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/nihilism\/' rel='post_tag'>Nihilism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/philosophical-pessimism\/' rel='post_tag'>philosophical pessimism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/philosophy\/' rel='post_tag'>Philosophy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/philosophy-of-mind\/' rel='post_tag'>Philosophy of Mind<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/polemics\/' rel='post_tag'>polemics<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/political-philosophy\/' rel='post_tag'>Political Philosophy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/politics\/' rel='post_tag'>politics<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/reflections\/' rel='post_tag'>Reflections<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/science\/' rel='post_tag'>science<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/secularism\/' rel='post_tag'>secularism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/social-philosophy\/' rel='post_tag'>Social Philosophy<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/social-psychology\/' rel='post_tag'>Social Psychology<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/society\/' rel='post_tag'>society<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/stoicism\/' rel='post_tag'>Stoicism<\/a><a href='https:\/\/danielbrynmor.com\/tag\/the-self\/' rel='post_tag'>the self<\/a>"},"readTime":{"min":1,"sec":54},"status":"publish","excerpt":""}]